Arnaud Paole (d. c. 1726) (Arnont Paule in the original documents; an early German rendition of a Serbian name or nickname, perhaps Арнаут Павле, Arnaut Pavle) was a Serbian hajduk who was believed to have become a vampire after his death, initiating an epidemic of supposed vampirism that killed at least 16 persons in his native village of Medwegya, located at the Morava river near the town of Paraćin.

His case, like the similar case of Peter Plogojowitz, became famous because it was officially investigated and documented by Austrian physicians and officers, who confirmed the reality of vampires. Their report of the case was distributed in Western Europe and contributed to the spread of vampire belief among educated Europeans.

In 1732, three Austrian medical officers were dispatched from Belgrade to investigate reports of an outbreak of vampirism in the nearby Serbian village of Medvegia. The exhumation of the corpses involved was delayed until their arrival.

After arriving at the village, the officers were told by villagers that the problem had actually started five years before with the death of Arnaud Paole (Arnold Paul). Paole had died after falling off a hay wagon and breaking his neck.

A few weeks after his burial, people had begun complaining of him coming to them at night, and four of these people had soon died afterwards. It was remembered that, before he had died, Paole had once talked about being attacked by a vampire in Turkish held southern Serbia during his military service. He had said that he’d destroyed this vampire.

He also had said that he ate earth from the vampire’s grave and smeared the vampire’s blood on his own body so that he himself would not become a vampire when he died.

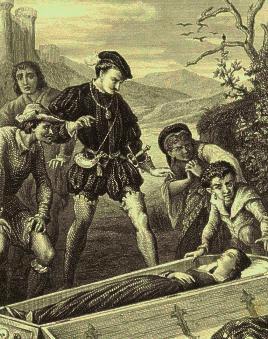

The villagers had decided that the latter two remedies had failed. Forty days after Paole’s burial, his body had been exhumed and found to be in a fresh condition with fresh blood having leaked from the mouth, nose, ears and eyes, and the corpse’s shirt and cloth covering were bloody. This had been taken as final proof that Paole was a vampire.

A stake was driven through the heart, causing a loud moan to issue from the rhroat, and the wound bled profusely. The corpse was then cremated. The ashes were returned to the grave. Not taking any chances, the villagers had next exhumed the four corpses of Paole’s victims, also staking and cremating them.

There had been no further problems from vampires for about the next five years, until about three months before the medical officers were sent to the village. At that time, a 60 year old woman named Miliza had died following three months of illness.

After her death, sixteen more deaths had followed. In one case, a 21 year old woman named Stanoicka, had woke up at midnight with a scream. She said she’d been attackeded by a 16 year old boy named Milloe who had died nine weeks before, following a three-day illness.

Stanoicka had then felt that her throat was being throttled by Milloe, and afterwards became greatly ill. She died three days later. Twelve of the seventeen total cases clearly involve a short but fatal illness. Besides Miliza, there is also one other case of illness lasting 3 months. (The circumstances of death for the remaining three are not given.)

The villagers had decided that this recent plague was initiated by Miliza after her death. It was believed that, five years before, she had eaten mutton from sheep that the vampire Arnaud Paole had preyed upon.

On the same day that the three medical officers arrived, all seventeen corpses were exhumed. Five of the seventeen bodies were found to be decomposed. But the rest, who included Miliza, Stanacka, and Milloe, were found to be in “the condition of the vampire.”

The medical officers dissected the corpses and verified that the internal organs were fresh and contained fresh blood. The officers found the evidence of vampirism to be quite convincing. The twelve bodies in “fresh” condition were then decapitated and cremated by hired gypsies. The ashes were thrown into the nearby Morava River.

Various versions of the official report by the chief medical officer to the Habsburgh emperor of Austria and Hungary, all titled Visum et Repertum (“Seen and Discovered”), were printed in newspapers in England and elsewhere that same year, 1732.

The sources are Vampires, Burial, and Death by Paul Barber and Dom Augustine Calmet’s Treatise on Vampires and Revenants.